In America’s healthcare system, transportation is often the forgotten link. A patient might have excellent insurance, an upcoming appointment with a top-tier specialist, and a treatment plan ready to go—but none of that matters if they can’t get to the clinic.

That’s where Volunteer Driver Programs (VDPs) come in. These programs, often run by nonprofits, local governments, or health organizations, offer a practical, low-cost way to get people to and from medical appointments, especially in areas where public transit is unreliable or nonexistent.

In this blog post, we’ll unpack what VDPs are, why they matter, how they operate, and the growing role they play in the U.S. health system. We’ll also look at real data and discuss their future in an aging and increasingly mobile nation.

What Is a Volunteer Driver Program?

A Volunteer Driver Program recruits individuals—often retirees or civic-minded residents—who use their own vehicles to transport people in their community. These aren’t rideshares or professional transportation services. They’re community-run, often small in scale but large in impact.

Typical Features:

-

Pre-scheduled rides to medical appointments or essential services.

-

Reimbursement for mileage (not pay), based on IRS standard mileage rates.

-

Insurance coverage provided by the organizing agency.

-

Eligibility screening for riders, focusing on seniors, people with disabilities, low-income individuals, or rural residents.

In many areas, these are the only transportation options that combine flexibility, personal touch, and affordability.

Why It Matters: Transportation as a Health Barrier

Transportation barriers are a leading reason people miss medical appointments in the U.S. According to the American Hospital Association, 3.6 million people in the U.S. annually do not receive medical care because they lack a ride.

Let that sink in. Millions are missing care—not because of a lack of providers or insurance, but because they simply can’t get there.

This affects:

-

Rural residents, who may live hours from the nearest hospital.

-

Low-income patients, who can't afford rideshare or taxis.

-

Elderly people, who may not drive anymore.

-

Disabled individuals, who need help getting to accessible services.

Volunteer Driver Programs step in where public transit doesn’t reach and where commercial options are either too expensive or unavailable.

Real-World Impact: Numbers That Tell a Story

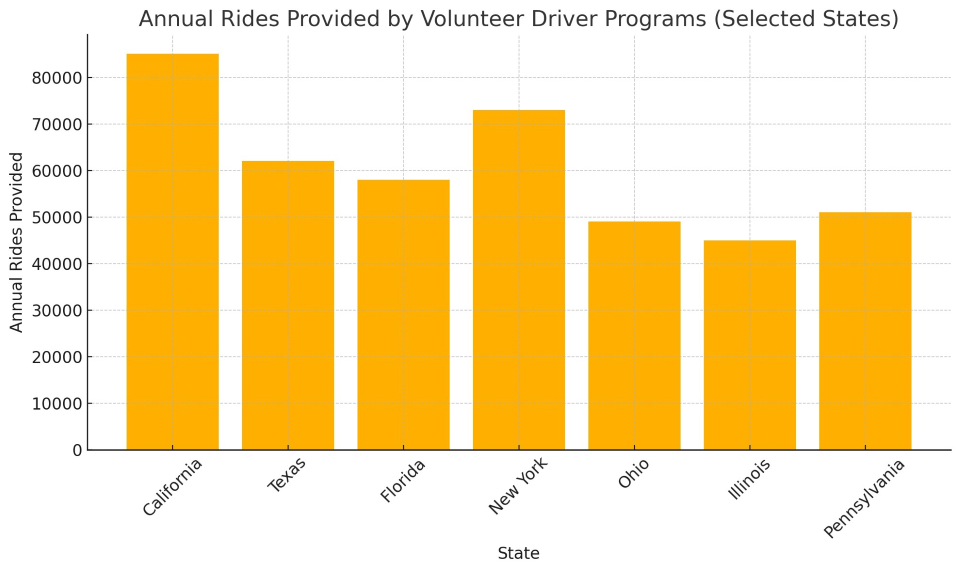

To understand the scope of these programs, let’s look at data from a sample of state-based VDPs:

Annual Rides and Active Volunteers by State

These numbers represent more than just logistics. Each ride is a cancer screening, a dialysis session, a mental health appointment, or a follow-up after surgery.

As the chart above shows, states with larger urban-rural divides or aging populations tend to operate at higher volumes. California, with its mix of dense cities and vast rural counties, tops the list.

How Volunteer Driver Programs Operate

Most VDPs function under a nonprofit umbrella or through Area Agencies on Aging. Some are tied to hospital systems or funded by federal transit grants.

Here's how a ride usually works:

-

Request: A rider contacts the program in advance—usually 48-72 hours before their appointment.

-

Match: The coordinator assigns a volunteer based on availability, distance, and ride needs.

-

Ride: The volunteer picks up the rider, takes them to their appointment, waits if necessary, and brings them home.

-

Reimbursement: Volunteers log their miles and are reimbursed monthly.

Some programs also offer recurring rides for patients undergoing regular treatments like chemotherapy or dialysis.

What Makes These Programs Work?

1. Community Engagement

Volunteer drivers often say they get as much out of the experience as the riders do. Many form friendships with the people they transport. This reduces social isolation for both parties.

2. Flexibility

Because volunteers use their own vehicles and set their own schedules, the programs can stretch limited budgets further than any for-profit service ever could.

3. Cost-Efficiency

According to the National Volunteer Transportation Center, most programs operate at less than $10 per ride, including insurance, scheduling, and reimbursements. That’s dramatically cheaper than paratransit or medical taxis.

Challenges and Limitations

Despite their value, VDPs face structural and operational challenges:

Aging Volunteer Base

Many drivers are seniors themselves. As they age out of the program, recruiting younger drivers has proven difficult.

Insurance and Liability

Concerns about accidents or personal liability deter potential volunteers, even when the programs offer secondary insurance.

Funding Instability

VDPs often rely on grants or donations. In lean budget years, services may be cut, limiting access for vulnerable populations.

Scheduling Bottlenecks

Unlike Uber, there’s no instant app. Ride coordination takes time and manpower—another strain on small nonprofit teams.

Government Support and Policy Role

VDPs often receive federal funding through:

-

FTA Section 5310 Grants: These support transit services for seniors and people with disabilities.

-

Medicaid NEMT Programs: In some states, VDPs are subcontracted to fulfill Non-Emergency Medical Transportation benefits.

-

State DOT and Aging Agencies: Provide grants or operational support at the state level.

Still, many program leaders argue more consistent funding, insurance protections, and public awareness are needed.

Looking Ahead: The Role of VDPs in a Changing Healthcare Landscape

With the U.S. population aging rapidly—20% will be over 65 by 2030—demand for medical transportation will only rise. Meanwhile, trends in home care, telehealth, and chronic disease management all point to the need for better, more flexible support systems.

Volunteer Driver Programs are uniquely positioned to meet that need. They are:

-

Scalable: With funding and support, they can grow.

-

Replicable: Communities of all sizes can implement them.

-

Sustainable: When managed well, VDPs can deliver consistent impact with minimal cost.

In the U.S. healthcare system, access remains one of the biggest hurdles to equity. Volunteer Driver Programs aren’t flashy, but they are effective. They connect people not just to appointments—but to independence, dignity, and better health outcomes.

Investing in these programs isn’t charity. It’s smart public health policy.