When people think about healthcare access in the United States, the conversation often starts with insurance coverage and costs. But there's another layer that's just as crucial: physical accessibility. It’s a simple concept that’s surprisingly complex in practice—can people physically get to the healthcare services they need?

Physical accessibility refers to the ability of individuals to enter, navigate, and receive services at healthcare facilities. It includes the geographic proximity of clinics or hospitals, the availability of transportation, and the physical design of the facilities themselves. In the U.S., physical accessibility remains one of the most uneven aspects of healthcare, often ignored until it becomes a crisis.

Why Physical Accessibility Matters

Access to care isn't just about having health insurance. If someone can’t get to a provider because of distance, lack of transportation, or disability barriers, insurance means very little. The consequences are severe:

The issue is especially urgent in communities already struggling with health disparities—rural areas, low-income neighborhoods, and populations with disabilities.

Breaking Down Physical Accessibility

To better understand the issue, here’s a breakdown of the main elements that make up physical accessibility in healthcare:

1. Geographic Location of Facilities

Healthcare deserts—regions with few or no healthcare facilities—are a growing problem in the U.S. Many rural counties have no hospitals at all. And in urban settings, some neighborhoods have an overconcentration of facilities while others have virtually none.

According to a report by the National Rural Health Association, people living in rural areas must travel 30 to 60 minutes or more for emergency care. That’s not just inconvenient—it’s dangerous.

2. Transportation Barriers

Even if a clinic is 10 miles away, that distance becomes insurmountable without a car or public transit. An estimated 3.6 million Americans miss medical appointments annually due to transportation issues, according to the American Hospital Association.

Public transportation, where available, often doesn’t align with clinic hours or locations. Rideshare programs like Uber Health have made inroads, but they are not universally available and may not serve those with mobility issues.

3. Accessibility for People with Disabilities

People with physical, sensory, or cognitive disabilities face barriers that go beyond getting to a facility. Inside many healthcare buildings, they may find:

-

Inaccessible exam tables

-

Lack of sign language interpreters

-

Confusing layouts or poor signage

-

Staff untrained in disability etiquette or care

Despite the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requiring public accommodations, a 2019 study in Health Affairs found that more than 80% of physicians were not fully confident in their ability to provide the same quality of care to patients with disabilities.

4. Facility Design and Layout

Accessibility doesn’t stop at the door. A poorly designed facility can frustrate and even endanger patients. Considerations include:

-

Wide hallways and doorways for wheelchairs

-

Clear wayfinding signs

-

Elevators with braille and audio prompts

-

Accessible restrooms and parking

Failing to meet these standards doesn’t just limit access—it can discourage people from ever returning.

State-by-State Accessibility Disparities

To illustrate the gaps in accessibility, let’s look at data from five major states:

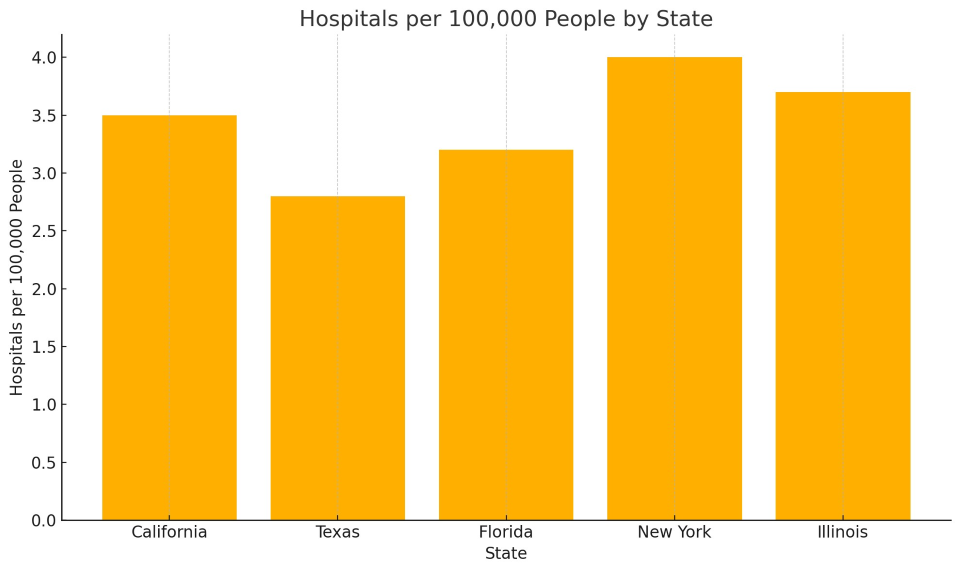

Now here’s a visual snapshot of hospital density:

These differences affect how quickly residents can access care. Texas, for example, has both fewer hospitals per capita and longer distances to reach them—highlighting the challenges faced in many Southern and rural regions.

Real-World Impact

Case 1: Rural ER Closures

In 2020, the only hospital in Blakely, Georgia shut down. The next nearest emergency department? Over 30 miles away. For someone having a heart attack or stroke, that drive can be fatal.

Case 2: Urban Transit Gaps

In parts of Detroit, residents without cars must take two or three buses—and several hours—to reach a primary care physician. Many give up and use emergency departments for routine care, driving up costs and wait times.

Case 3: Disability Inaccessibility

A wheelchair user in Los Angeles reported being turned away from a local urgent care clinic because the exam room couldn’t accommodate their chair. This isn’t an isolated story—it’s an indictment of how facilities often overlook basic design principles.

What the U.S. Health System is Doing (and Not Doing)

Efforts Underway

-

Telehealth Expansion

During the pandemic, virtual care became a lifeline, especially for patients in remote areas. It can’t replace all in-person care, but it’s a major help for chronic disease management, therapy, and follow-ups.

-

Mobile Clinics

Some cities and nonprofits are bringing care directly to patients with mobile units. These can provide vaccinations, screenings, and even dental care.

-

Policy Pushes for ADA Compliance

Some state health departments have begun requiring ADA-compliant audits for licensed facilities, but enforcement is inconsistent.

What’s Still Missing

-

Funding for rural hospitals: Many are still closing due to financial pressures.

-

Affordable non-emergency transport: Medicaid’s transportation benefit (NEMT) helps, but many states restrict it or underfund it.

-

Training for healthcare staff: Disability competence isn’t consistently included in medical education.

-

Urban infrastructure planning: Few cities integrate healthcare access into transit and zoning decisions.

Where We Go From Here

Improving physical accessibility in healthcare isn’t just about building more hospitals. It’s about smarter, more inclusive design and policy. Here's what can help:

-

Health Equity Mapping Tools

Systems like the CDC’s PLACES project help identify communities with low access to care and guide targeted investments.

-

Accessibility Grants and Incentives

Government and private grants can support facility upgrades for ADA compliance and rural service expansion.

-

Integrated Transport & Health Planning

Transit agencies and health departments should collaborate to ensure that people can physically reach care without unreasonable effort or cost.

-

Community-Based Health Workers

Trained workers embedded in communities can bridge gaps in access by providing education, helping with logistics, and even delivering basic care.

Physical accessibility is a foundational aspect of healthcare equity. If someone can’t physically get to a provider, all the insurance coverage, technology, and innovation in the world won’t help.

It’s time the U.S. health system starts treating physical accessibility not as an afterthought, but as a core metric of healthcare quality—because care that’s out of reach isn’t care at all.