A Closer Look at Its Role in the U.S. Health System

In the U.S. healthcare system, treatment planning is more than paperwork—it’s the backbone of patient-centered care. It ensures that care is not only clinically appropriate but also coordinated, efficient, and aligned with patient needs and goals. Especially in a system as complex and specialized as that of the United States, treatment planning helps bring order to what could otherwise be a fragmented experience.

What is a Treatment Plan?

A treatment plan is a written or digital document that outlines a patient’s medical condition, the goals of treatment, specific interventions to be used, and timelines for review. It is created collaboratively between healthcare providers and the patient, often involving a multidisciplinary team.

Treatment plans serve as both a clinical roadmap and a communication tool—ensuring that everyone involved knows what the objectives are, what steps will be taken to reach them, and how success will be measured.

Why Treatment Planning is Critical

In the U.S., patients often navigate care across various facilities and providers—primary care doctors, specialists, hospitals, rehabilitation centers, and outpatient services. Without a clear treatment plan, this journey can become disjointed.

Good treatment planning:

-

Reduces unnecessary or duplicate services

-

Improves patient adherence and satisfaction

-

Clarifies goals for both providers and patients

-

Ensures better continuity of care

-

Increases efficiency in resource use

Core Components of a Treatment Plan

See the table “Treatment Plan Components” above for a breakdown of the core elements.

Let’s go deeper into what each component really involves in a clinical setting:

1. Assessment

This includes a comprehensive review of the patient's current health status, history, lifestyle, and personal preferences. This phase might involve physical exams, lab tests, psychological evaluations, and intake interviews.

2. Diagnosis

After assessment, a clear clinical diagnosis is made. For chronic illnesses or complex conditions, multiple diagnoses may be involved (e.g., diabetes with depression).

3. Goal Setting

This step aligns medical goals with patient preferences. For example, while a clinician might focus on reducing blood pressure to safe levels, a patient may prioritize being able to play with their grandkids without shortness of breath.

4. Intervention Planning

This is the treatment strategy—what medications, therapies, surgeries, or behavioral changes will be used to meet the goals.

5. Implementation

The treatment plan is put into action. This phase often involves scheduling appointments, coordinating between providers, and ensuring that all elements of care are initiated.

6. Monitoring and Evaluation

Treatment isn't static. Providers need to track how the patient is responding, using check-ins, follow-up tests, or patient-reported outcomes.

7. Revision and Continuation

If the treatment isn't working or the patient’s needs change, the plan gets updated. This flexibility is especially important in long-term and chronic care.

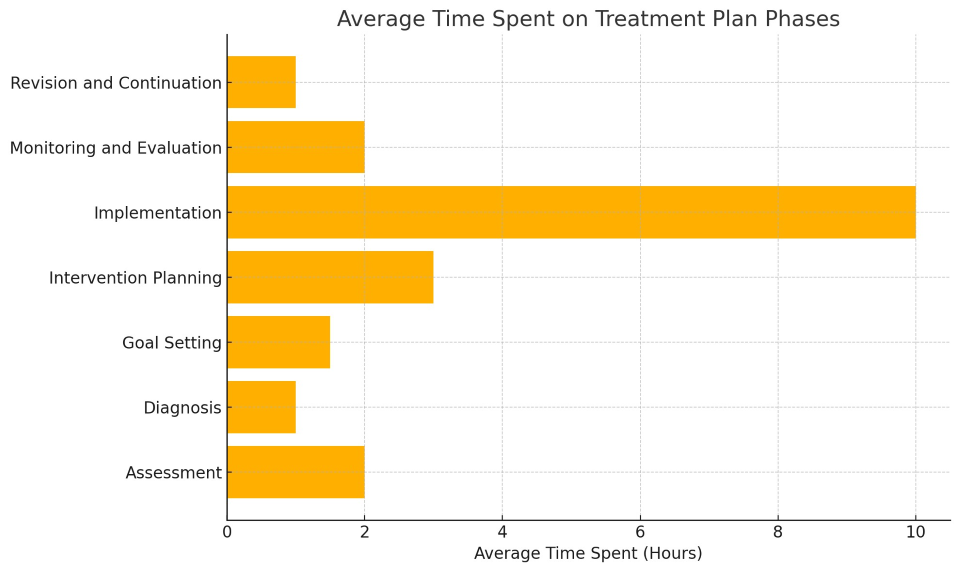

Time Spent on Treatment Planning Phases

As shown in the bar graph above, implementation takes the largest share of time, but planning, assessment, and monitoring are also time-intensive. While these steps may seem secondary, they are critical to long-term success.

Legal and Ethical Considerations

Treatment plans also carry legal weight. In the U.S., they are part of a patient’s official medical record. That means they must be:

-

Accurate: Errors can have legal consequences.

-

Updated: Stale plans can lead to poor outcomes and liability.

-

Accessible: Under HIPAA, patients have a right to access and understand their plan.

For mental health professionals and addiction counselors, treatment plans are often required to meet state licensure or insurance reimbursement standards.

Insurance and Financial Impact

Most U.S. health insurance providers—including Medicaid and Medicare—require detailed treatment plans to authorize coverage. These plans help justify:

-

Why a procedure or medication is necessary

-

How long a treatment is expected to last

-

How progress will be measured

In some cases, insurance companies may deny coverage if a treatment plan is missing or inadequate. This forces providers to strike a balance between clinical documentation and bureaucratic demands.

Common Challenges in the U.S. Health System

Despite their importance, treatment plans are not always executed well. Here are some persistent problems:

1. Fragmented Care

Patients often move between providers who use different electronic health record systems. Without interoperability, the treatment plan may not follow the patient.

2. Time Pressures

Primary care doctors in the U.S. average 15-minute visits. That leaves little time for collaborative goal setting or detailed planning.

3. Health Literacy Gaps

Many patients don’t fully understand their diagnoses or treatment goals. When plans are full of jargon or written at a high reading level, adherence drops.

4. Cost Barriers

Even the best plan won’t work if the patient can’t afford the medication, therapy, or follow-up care.

Trends Shaping the Future of Treatment Planning

As the healthcare industry shifts toward value-based care, treatment planning is evolving too. Here’s how:

Personalized Plans via Big Data

AI-powered platforms are beginning to tailor treatment suggestions based on large datasets and predictive modeling. Instead of relying solely on clinical guidelines, plans can now be personalized using outcomes from thousands of similar cases.

Integrated Care Teams

Models like patient-centered medical homes (PCMH) and Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) emphasize team-based planning. These approaches reduce duplication and improve coordination.

Remote Monitoring

Wearables and mobile health apps now allow clinicians to adjust treatment plans in real time based on data collected outside the clinic—like blood pressure, heart rate, or mood tracking.

Treatment planning is not just an administrative task—it’s the strategic foundation for every successful patient outcome. In the sprawling and often fragmented U.S. health system, it brings structure, clarity, and accountability.

It helps providers work smarter, helps patients feel heard and empowered, and helps the system use resources more wisely. And as technology and models of care evolve, so too will the tools and strategies we use to plan for better health.

Whether you're a healthcare provider, a patient, or a policymaker, the takeaway is clear: a good plan is good medicine.